Morse Code – Why Bother Learning It?

Why would anybody want to waste time learning Morse Code? Specially now, with modern technology. It’s old technology, isn’t it? From back when there was no reliable way to communicate over long distances. So what’s the point of it? And what exactly is Morse Code anyway? And what’s so special about it that people have been using it for well over a hundred years? Mmm … questions, questions, questions …

Okay, let’s see if we can answer some of those questions. Yes, it’s old technology, in fact it first appeared in the early nineteenth century and was an attempt to transmit language using only electrical pulses. People had been experimenting with electricity and electromagnets for some time by then, and the time was ripe for someone to harness the power of electricity to create virtually instantaneous communication.

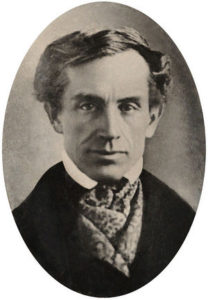

The code created by Samuel Morse … and others

To be fair to the others, Morse wasn’t the only one to advance this field. Morse worked with Alfred Vail and the physicist Joseph Henry to develop an electrical telegraph system. William Cooke and Charles Wheatstone in Britain developed an electrical telegraph that used electromagnets in its receivers, for which they obtained an English patent in June 1837. Meanwhile, Carl Friedrich Gauss and Wilhelm Eduard Weber, as well as Carl August von Steinheil, used codes with varying word lengths for their telegraphs. So there was a lot of experimentation going on in various parts of the world at that time.

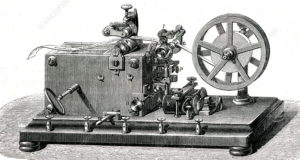

The early attempts at telegraphy weren’t quite the same as Morse’s later and better known method. The earlier Morse system, which was first used in about 1844, was designed to make indentations on a paper tape whenever the electric current was flowing. When an electrical current was received, an electromagnet caused a stylus to be pushed onto a moving strip of paper tape, resulting in an indentation. Once the current was interrupted, a spring caused the stylus to be retracted.

Morse code was developed so that the telegraph operators could translate the series of indentations into text messages. In the earliest iteration of the code, Morse planned to use only numbers, and with the aid of a code book the operator could discover which words were represented by the numerical codes sent. It was Alfred Vail, in 1840, who introduced letters to the code, as well as some special characters, so that the code could be more easily and more widely used.

The earliest form of Morse code, 1844

He estimated the frequency that letters were used in the English language by counting the movable type he found in the type-cases of a local newspaper, and assigned the shorter codes to the most frequently used letters. This code became known as Morse landline code or American Morse code, and was the forerunner of what we know today as Morse Code.

It wasn’t long before telegraph operators realised that the machine clicked when the armature moved, so it was possible to translate the clicks they were hearing directly, instead of waiting to read the indentations in the paper strip. Consequently, an operator could be writing the letters down almost as fast as the sending operator sent them. With a few refinements over the next few years, this resulted in the Morse Code we’re all (at least vaguely) familiar with.

Morse code was used extensively in the 1890s for early radio communication before it was possible to transmit a person’s actual voice. And it was very widely used in the early 20th century since most international communication used Morse code on telegraph lines, as well as via undersea cables and for radio communication. So it’s no exaggeration to say that Morse code was not just an interesting innovation but a very important development in long distance and even international communications.

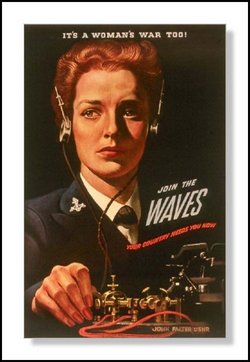

Morse code in wartime

Beginning in the 1930s, both civilian and military pilots were required to be able to use Morse code, both for communications and to identify navigational beacons, which transmitted two- or three-letter ID symbols in Morse code.

Morse code played quite a significant role in World War II, using encrypted messages, specially from ship-to-ship and ship-to-naval base, since voice radio at sea was, at the time, quite limited in range, not to mention the lack of security it offered. And you don’t have to be a WWII film fanatic to realise just how vital Morse code communication was between agents in the field.

Morse code was still used as an international standard for maritime distress until 1999 when it was replaced by the Global Maritime Distress and Safety System. With modern telecommunications and mobile phone technology, Morse code has been phased out globally in recent years, though the United States Air Force still trains ten people a year in Morse. Knowledge of Morse code is now the domain of the enthusiast. It has, for many years, been the domain of the ham radio enthusiast, but even that use is now diminishing.

Some notable cases of Morse code saving the day

There have been many times when a simple SOS signal has been a lifeline that has saved people in distress. If you’re marooned on an island all you have to do is position rocks in the shape of these three letters and hope that a passing aircraft spots the message. Okay, it’s not strictly Morse, but it is a visual version of the Morse distress signal, which is ••• — — — •••. And it might be more effective than writing HELP in huge letters … or maybe not, who knows?

There have been many times when a simple SOS signal has been a lifeline that has saved people in distress. If you’re marooned on an island all you have to do is position rocks in the shape of these three letters and hope that a passing aircraft spots the message. Okay, it’s not strictly Morse, but it is a visual version of the Morse distress signal, which is ••• — — — •••. And it might be more effective than writing HELP in huge letters … or maybe not, who knows?

This signal (SOS) can also be sent in various other ways. For example, flashing a mirror on an off in the form of dots and dashes (more correctly known as dits and dahs, by the way), toggling a flashlight on and off, tapping on a metal pipe, even turning a radio on and off as though it were a Morse key. The one constant in most of these things is that no power is needed – if you have access to an empty tin can and a way to open it up and flatten it out, you have a shiny ‘mirror’ that can be used to send a message to someone far off, and if you have a spanner or a stone you could tap an SOS on a metal pipe if you were trapped in a collapsed building, for example.

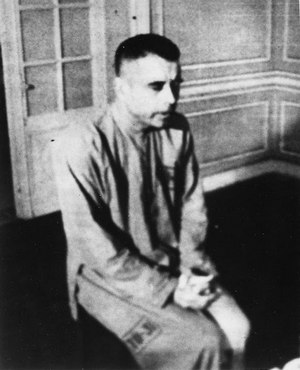

Another notable example of Morse being used constructively is the case of Jeremiah Denton, a prisoner of war during the Vietnam conflict. He was paraded on television in 1966 by his North Vietnamese captors for propaganda purposes, but he used the opportunity to send a message of his own; he blinked his short message in Morse code … TORTURE. There have also been cases of radio operators who after having suffered strokes were able to communicate with their families or carers by blinking their eyes Morse code-style to convey their wishes.

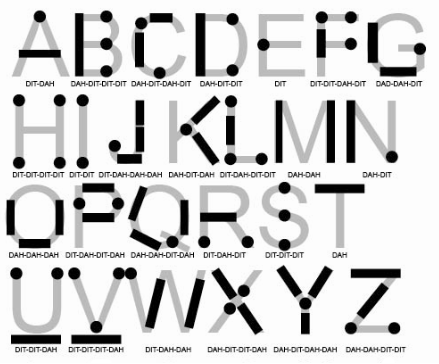

The table below lists all the Morse Code values for the letters of the alphabet, as well as a mnemonic to help you get a feel of the sound. I’ve used lower case letters where there is a ‘dit’ sound, and upper case where there is a ‘dah’. And of course each mnemonic uses the letter it represents, usually at the beginning.

It also shows the number of the letter in the alphabet, and the NATO alphabet. Having them in the same table might help you learn those two things much easier, assuming you didn’t already know them.

| No. | Letter | Morse Code | Mnemonic | NATO Alphabet |

| 1 | A | a-PART | ALPHA | |

| 2 | B | BE a good boy | BRAVO | |

| 3 | C | CO-ca CO-la | CHARLIE | |

| 4 | D | DOG did it | DELTA | |

| 5 | E | egg | ECHO | |

| 6 | F | fetch a FIREman | FOXTROT | |

| 7 | G | GOO-GLE ad | GOLF | |

| 8 | H | hip-it-y-hop | HOTEL | |

| 9 | I | I did | INDIA | |

| 10 | J | he's J. JONAH JAMESON | JULIET | |

| 11 | K | KAN-ga-ROO | KILO | |

| 12 | L | a LIGHT is lit | LIMA | |

| 13 | M | MMM, MMM | MIKE | |

| 14 | N | NOR-ma | NOVEMBER | |

| 15 | O | OH! MY! GOD! | OSCAR | |

| 16 | P | a POO-PEE smell | PAPA | |

| 17 | Q | GOD SAVE the QUEEN | QUEBEC | |

| 18 | R | ro-TA-tion | ROMEO | |

| 19 | S | si-si-si | SIERRA | |

| 20 | T | TEE | TANGO | |

| 21 | U | un-i-FORM | UNIFORM | |

| 22 | V | vic-to-ry VEE | VICTOR | |

| 23 | W | the WORLD WAR | WHISKY | |

| 24 | X | X marks the SPOT | X-RAY | |

| 25 | Y | YEL-low YO-YO | YANKEE | |

| 26 | Z | ZSA ZSA did it | ZULU |

So … why bother with it?

This brings us to the question, if this system has now been almost completely shunted off into its place in communication history, then why even bother to learn it? Well, apart from the obvious (it’s always fascinating to learn something new), learning Morse code is a chance to exercise your memory.

It’s important though to remember that you don’t learn Morse by looking at the dots and dashes in a list, you learn it by listening to the dits and dahs as they are transmitted. So the best way to learn Morse is to listen to it. Download a Morse app to your phone (try Morse Mania, it’s very good) – you’ll be able to hear a few letters at a time and click on the right one [on the keyboard] to move forward. As you get more familiar with a few letters, the app will add two or three more. It’s all done by listening, that’s the important thing to keep in mind.

It’s also important to realise that you won’t master Morse just by learning the letters. Even if you get to the point where you can tap out a message and listen to a minute or two of Morse code and know what it means, it will never fully prepare you for receiving the code in real life – that’s another skill altogether. Some operators send at a far faster rate than you could possibly understand, unless you’re very experienced.

Even if you’re good, there will be times when you miss a letter because it seems to make no sense, and if you don’t then leave a space [as you’re transcribing] you’ll end up missing the following several letters due to your confusion. Soon as you know you’ve missed a letter (or a word), just leave a space and move on. You might well make sense of it later, when you review the context of what you’ve written.

The problem with decoding Morse as it’s transmitted to you is that each letter follows on from the last so quickly … yeah, that’s a real problem! Knowing the letters is okay, but knowing them all well enough to decode a message is something else altogether!

If you’re serious about improving your Morse skills, check out this page. If you want to practise receiving Morse and you don’t have a fellow student to work with, this could be your dream come true. You’ll find practice files in audio, from 5 wpm (words per minute) to 40 wpm, and lots of them. You can download them and listen to them at your leisure! That should keep you busy for quite a while, and if you just stick to the 5 wpm files till you’re ‘fluent’ with a few of those you will have achieved quite a decent level of skill.

Morse as a memory exercise

If you set yourself a target of learning Morse, and then a target of becoming more proficient, you’ll have an interesting memory exercise. It’s something you can do every day, if you like, or just occasionally, whenever you find the time. And if you find it an interesting challenge, you’ll enjoy it all the more. And hey, don’t forget how much you’ll enjoy decoding the messages you hear being tapped out on all those old war films!

This, just like various other memory exercises, is an excellent brain exercise. The more you use your brain, the more efficiently it works. I mentioned earlier how vital Morse code was during WWII, and this short video might give you some idea of the calibre of the people who used it. This lady is in her 90s now and she still remembers her Morse code (mostly!) after many, many years.

And if you’re wondering what happened to all those radio stations that used to send out and receive Morse code messages, check out this video. It’s a nostalgic look at the last Morse code maritime radio station in North America.